Basic concepts

RATIONALE. Evaluation and monitoring. Basic concepts

Environmental assessments are important environmental protection tools. By involving authorities and citizens and incorporating environmental reports, the potential environmental impacts of a planned project can be identified at an early stage and taken into consideration during the decision-making process (https://www.bmuv.de/en/topics/education-participation/participation/environmental-assessments-eia-sea#c19043). Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) are some of the various procedures that ensure that the environmental implications are taken into account before the decisions are made (https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/eapgreen-sea-and-eia.htm). Evaluation is a pillar of the European regulation on the conduct of plans, programmes and projects. These are key processes in the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) which applies to public plans and programmes. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is very similar to SEA except that it applies more specifically to the scale of private and public projects (https://www.era-comm.eu/EU_Legislation_on_Environmental_Assessments). These processes are based on Directive 2001/42/EC known as the SEA Directive.

Recent systematic reviews about the role of habitat and corridors for various animal taxa (Villemey et al., 2018; Ouédraogo et al., 2020), observed that a very small number of research studies have been built with a robust monitoring design, underlining among their recommendations for future research studies:

- Increase the study duration, the number of true spatial replicates and the spatial extent of the studies.

- Favour data collection before the intervention when studying the effect of management practices using, for example, BACI (before/after/control/intervention) or BAI (before/after/intervention) designs.

BACI approaches include time and impact factors, with a control site and a comparably impacted site, both represented by data before and after the impact. The BACI approach makes it possible to account for any natural or pre-existing differences between the sites, and thus to estimate the real effect of an impact variable between the control and the impacted site (Roedenbeck et al., 2007).

Monitoring and evaluation are activities undertaken to assess: i) the effectiveness of mitigation measures in reaching the goals for which they have been designed, and ii) the effects of the project on biodiversity conservation targets.

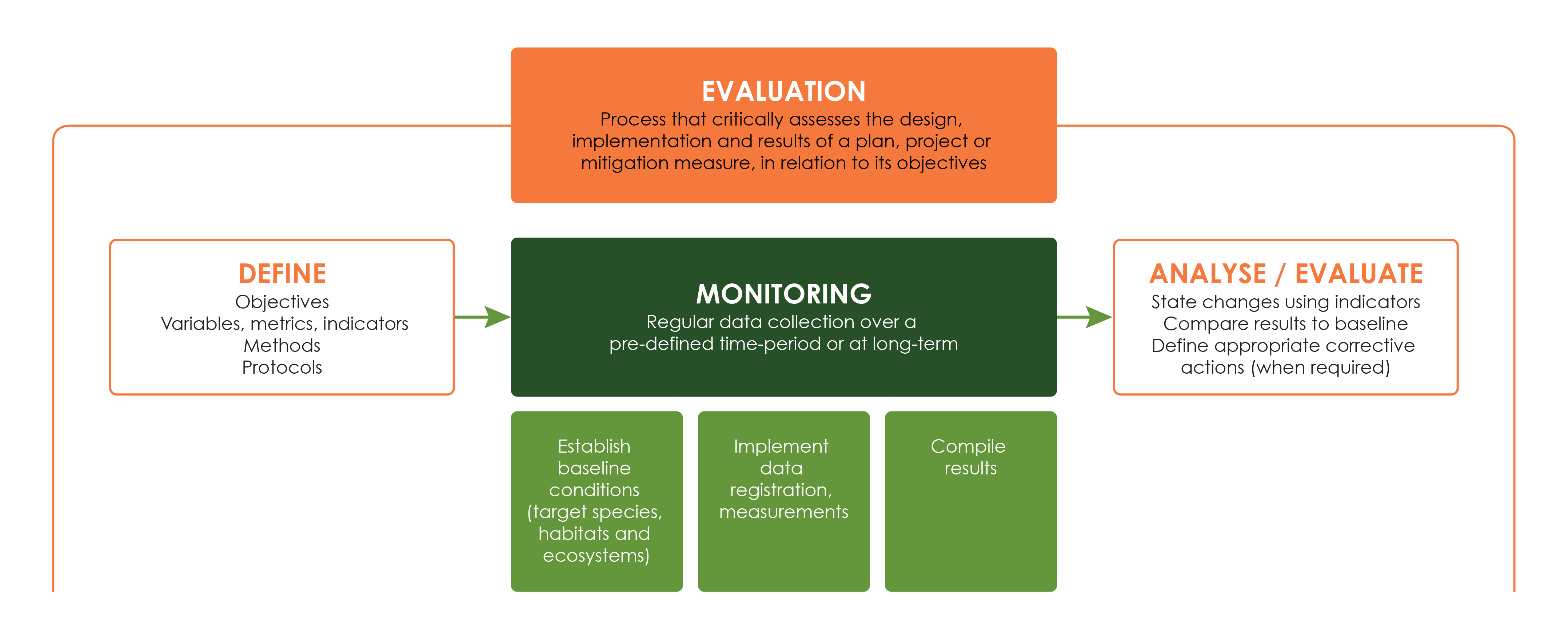

Although in practice ‘monitoring’ is used to refer to both evaluation and monitoring, these are different terms, and monitoring is an activity within the evaluation process. Both are complementary and part of a continuous process (Figure 6.1.1).

- Evaluation is a process that critically assesses, tests, and measures the design, implementation and results of a plan, project or mitigation action, in relation to its objectives. It can be conducted both qualitatively and quantitatively, to determine the difference between actual and desired outcome. In transport ecology, the aim of this process is to check whether a project and the mitigation measures applied have met their objectives in terms of reduction and compensation for impacts. A correct evaluation requires that objectives and their metrics are defined, and measured with an appropriate monitoring design. Evaluation is undertaken during the infrastructure operation phase and called in some countries ‘post-project analysis’. It requires data provided by monitoring (regular data collection over a pre-defined time-period or at long-term) and the application of a robust methodology design to collect unbiased data, where schemes developed in data collection and analyses are standardized and can be repeated.

- Monitoring is a process driven by the evaluation goals that combines repeated observations and measurements taken over time, usually to assess the temporal change in a parameter or in response to a disturbance/intervention or to quantify the performance of a plan, project or mitigation action against a set of predetermined indicators, criteria or objectives. In the framework of transport ecology, monitoring is a key tool which begins with the design of the monitoring plan. The first step therefore aimed at identifying the evaluation baseline and initial state of target species, habitats and ecosystems which is expected to be affected. Then monitoring determines changes of selected metrics required to perform the evaluation and registered them during the construction and operation phase.

This chapter focuses on monitoring and evaluation at the design, construction and operation phases and does not focus on the evaluation at strategic planning phase which must be also defined in association with SEA (see Chapter 2 – Policy, strategy and planning) nor in the maintenance phase. Additional information about inspection and monitoring tasks undertaken during maintenance can be found in Chapter 7 – Maintenance.

European legislation and country specific regulations, require an assessment of impacts on local biodiversity, and the design and application of measures to mitigate the impacts of transport infrastructure. These measures include actions to avoid, reduce or compensate for the impacts of any new infrastructure, and for upgrading and adaptation of existing infrastructure in some specific cases (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy to learn more about). Monitoring and evaluation should be defined in the initial steps of the transport infrastructure life cycle after a biodiversity baseline has been established and during the design phase in association with EIA. Monitoring and evaluation activities are then undertaken during the construction and operation phases of the project life cycle.

Monitoring associated to each evaluation (regardless of whether it is focused on infrastructure impacts evaluation or on mitigation measures effectiveness evaluation) must be defined through a 4-step hierarchical but iterative approach which ensures a consistency in the evaluation process. The examples below are focused on fauna crossing a road but may be equally applied to other mitigation scenarios and biodiversity targets (i.e., other habitats or ecosystems).

Step 1. Defining the evaluation objectives

What must be evaluated? For example:

- Did we reduce the collisions between animals and vehicles?

- Did target species use the wildlife passages?

- Do my mitigation measures ensure gene exchanges?

Step 2. Defining the variables, metrics and indicators to undertake the evaluation

What must be measured (variables)? How will we measure it (metrics)?

How will we evaluate changes over time and whether the objectives are fulfilled or not (indicators or KPIs). For example:

- What target species need to be monitored?

- What are the number of road kills over time?

- What is the number of animals crossing a wildlife passage?

- Do we have genetic diversity from both sides of my transport infrastructure?

- How often do I need to make my measurement?

Step 3. Defining the method for recording the parameters defined in step 2

Which method can be applied to obtain data needed? For example:

- Direct counting of dead animals on the field?

- Using camera traps on wildlife passages to register animal crossing?

- Sampling target species tissue to evaluate genetic diversity from both side of the infrastructure?

Step 4. Defining the appropriate scheme to implement the method proposed in step 3 for reaching the objective defined in 1

How the methods will be applied to guarantee we collect appropriate results? For example:

- Deploy enough field work to obtain the data needed?

- Deploy enough camera traps and apply appropriate techniques and time required for analysing images?

- Capture enough individual for obtaining appropriate number of DNA samples?

At each step, if the questioning process leads to a dead-end, the questioning process should come back to the upper rank in the process hierarchy (i.e., if no answer can be found at step 3, a new branch of step 2 should be explored). This process can lead to adaptation or strong refinement in the objective definitions. Although not comprehensive, this process can also help in designing good monitoring programmes that are based on evaluation objectives.